Shops, Restaurants, Kindergartens: One Year On From the Destruction of Self-Organised Structures in Katsikas Camp

One year ago, we shared an article outlining new measures being taken by the management of the so-named ‘Katsikas Hospitality Centre’. This included the sudden dismantling and burning of self-organised services and structures, established by camp residents. This included 5 supermarkets, 4 bakeries, 1 coffee shop, numerous repair shops, a kindergarten, and even personal gardens; these were taken apart, and the materials used to build them were burnt.

The last year has seen a continuation of strict measures imposed on camp residents. The impact of the closure of self-organised structures can still be felt today: in an increasingly restricted and authoritarian environment for those in camp, these small kiosks acted as accessible and affordable lifelines, both to users and those who ran them.

Several of the affected shop-owners and self-organised service providers spoke about their experience; you can hear their interviews on our Youtube channel. Most spoke to us anonymously out of fear of repercussions if identified by camp management.

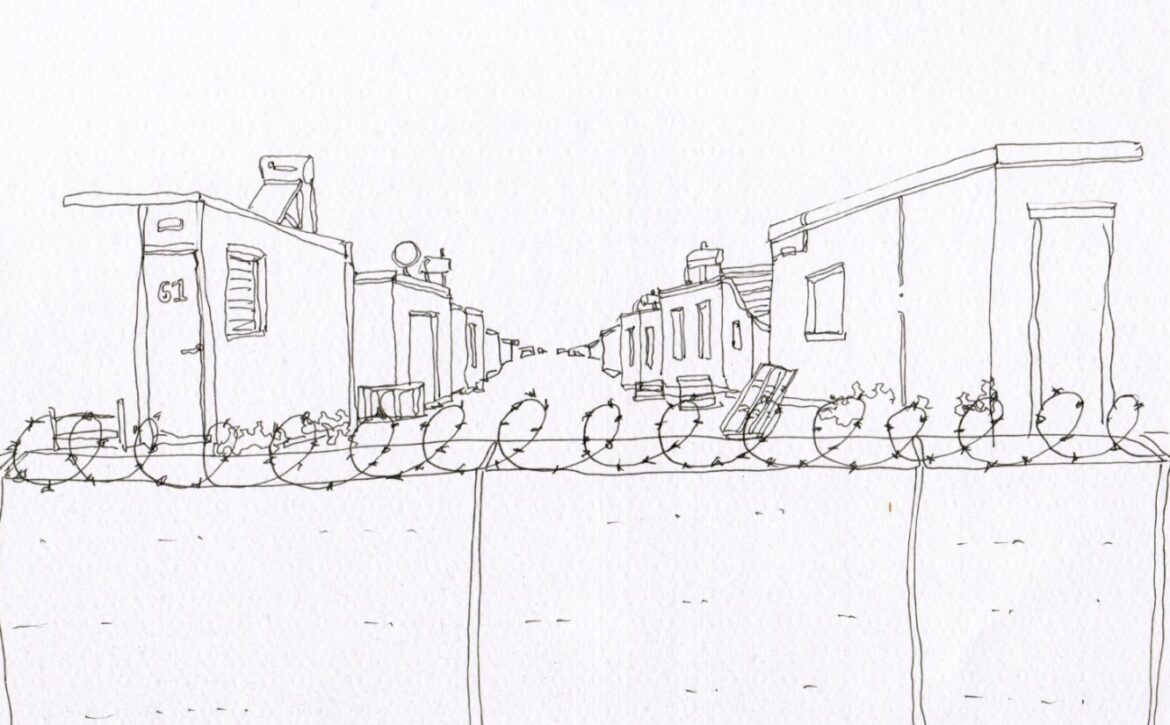

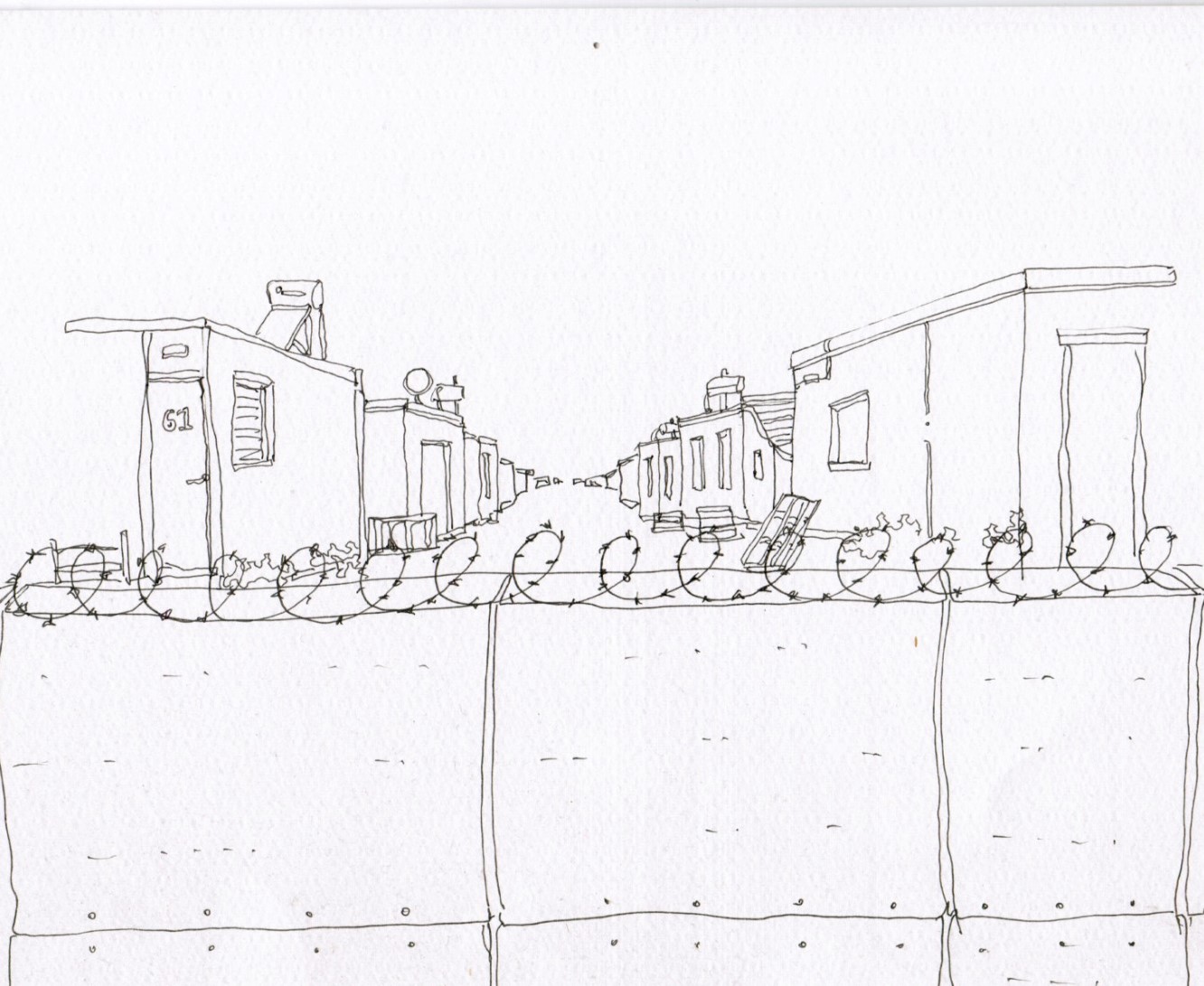

A depiction of Katsikas camp, drawn by May Elise Sturman.

The dismantling of a micro-economy

The forcible closure of the self-organised services in camp aggravated the financial situation of many within the camp. Two of the affected shop owners, who shared their experience under condition of anonymity, underlined the clear benefit of the services in alleviating some financial strain for both shop owner and customer. One, a baker, said:

The other, a supermarket owner, stated:

The need for these small, additional forms of income and the availability of affordable products was all the more stark due to cuts in financial support given to camp residents by the Greek government. In winter 2021, asylum seekers had all financial-support cut for 4 months without notice, only to be reinstated at half the initial amount: €420 reduced to €210. No additional payments were made in for missed months. In the words of the supermarket owner:

The shops as a support network

The shops not only provide small but essential incomes for the families of the shop owners at a critical time – they are also a lifeline for the residents of the Katsikas camp who shop there. Food and essentials in the camp shops are often priced significantly lower than in the shops in town and the surrounding area, and do not cost money to get to (as opposed to those in the nearest urban centre, for which individuals must pay the bus). Not only that, but the relationships that exist within the camp community make it possible for individuals in tough financial positions to ask for extensions on payment for basic goods.

As another shop owner put it:

You see, some families, they don’t have money. So we give them free, the things they need. Or if they say, “I will bring you after” – one month later, two months later, even three months later – of course we will give them! We don’t ask, or we don’t say anything. Because we trust them. We feel them. We know what is their situation. If they go to the city and tell to the supermarket, “I need these things and after, I will bring you the money.” What will they tell you? Nothing. Of course they will not give you the things you need. And because of these types of problems, we say, “keep the shops.”

Strategic boredom: strategies of suppression

Beyond financial support, self-organised services also served more abstract functions, no less crucial to the lives of those who used them. Mohammad Hossein, a camp resident who also ran a supermarket, expressed:

In providing local, affordable access to the products preferred by camp residents, supermarkets like Hossein’s provided an all-important yet simple notion: basic choice. Camp residents are provided with pre-cooked food, for which they queue once a day. Coupled with the Greek asylum process – a seemingly ceaseless, passive process of waiting and interrogation – and the increasingly strict measures imposed by camp management, camp residents are left with very little active scope for choice. The simple choice of cooking one’s own meal according to one’s tastes is a powerful thing, in a context where individual agency is systematically limited.

One camp resident, who ran a kebab shop, shed further light on the deeper use and need for services like his.

Beyond a support network, the self-organised services in camp provided, quite simply, something to do. According to a report by the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, a specific means of control used by Greek refugee camps is that of ‘strategic boredom’, where the stripping away at activities and strict measures of control by camp authorities is combined to keep camp residents idle and passive. It does not require much thought to view the destruction of these services as – at the very least – an unwitting example of this measure in action.

Nariman, one of 8 camp residents who ran a self-organised kindergarten, spoke similarly after the kindergarten’s container was forcibly closed by camp management.

The kindergarten not only catered to all-important childhood development through games and learning, but the child care allowed parents in camp to attend educational activities, employment opportunities, or to travel to the city some 30 minutes away for basic necessities. Again, this simple service provided camp residents with a greater degree of choice and freedom to facilitate their own solutions to their problems. This is now a far more complicated and deliberately restricted prospect.

One Year On: Impacts of Forced Closure

One year on, the long-term impact of this forced closure of self-organised services in camp is being felt acutely. With now more than double the number of camp residents than at the time of the services’ destruction, the need for accessible and affordable services is paramount. Transport to shops and services in the city of Ioannina, some 30 minutes away by bus, is simply not financially feasible for many. This is exacerbated by extremely limited financial support from the state. Though bicycles are an option for some, they are not widely available. This limited access to the city means there is no way to get basic items, such as ingredients, hygiene items, and baby care items in camp.

The closure of the self-organised services in camp constituted the first of a long-line of highly restrictive measures and the increase of camp security & authority. It was not long after closure that a 3-metre high wall was erected, topped with barbed wire, surrounding the perimeter of the camp and obscuring it from view. Security staff in camp has tripled, coupled with strict monitoring of exit and entry into camp via a system of recently instituted turnstiles. Residents are now expected to present their fingerprints to camp management once a week in an effort to monitor their movements, assess their dependency on the accommodation, and evict those who are no longer eligible for residency in camp. This mandatory check-in further aggravates the financial strain felt by many camp residents. It is especially difficult for those who seek seasonal work as a means of much-needed income out of the city. Seasonal workers need to return to camp to attend the weekly-monitoring, undermining the financial relief this work could otherwise provide.

Nariman put it simply:

Dignified solutions are possible. We call on the European Union to address the hunger in Greek refugee camps and the reduction of monthly allowances, and to condemn and address the neglect thousands of people are currently experiencing in one of its member states.

Author: George Washbourn

Editor: Esther ten Zijthoff